Half Double Article 1

What worked in the past won’t work in the future

Throughout human history, great progress has been made every time we questioned our basic assumptions

... Who says we can’t fly to the moon?

The same applies to the way we run our society and our companies in the western world.

As management consultants, we asked ourselves the following questions to challenge & develop our work

What assumptions have led to our increase in prosperity?

Are there assumptions that are outdated in our project management?

What new principles would create further progress and growth?

The next chapter elaborates on our reflections. Do they make sense to you? Can you relate?

The past was built on efficiency and optimization

For thousands of years, the human race lived as hunter-gatherers and the simple notion of agriculture didn’t dawn on anyone. It was a giant leap when we stopped living like nomads and started staying put. We went from short-sighted thinking and eating everything here and now to gathering reserves, sowing and cultivating, and keeping and breeding animals. This stage change multiplied our production by the hundreds. Today, a relatively small percentage of the world’s population feeds the rest.

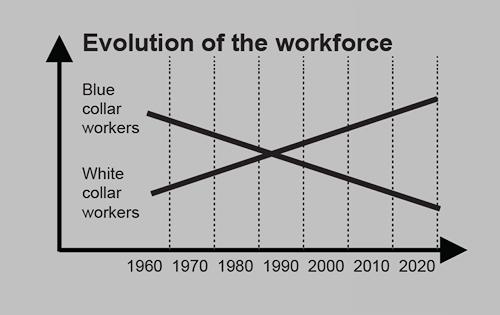

Henry Ford’s transformation of car manufacturing from workmanship to industry, marked the beginning of the efficiency-driven era. Industrialization was founded on four simple principles: standardization, reproducibility, specialization, and the division of labor. Throughout the sixties, quick changeovers became increasingly important because multiple suppliers offered similar products.

During this period, Toyota factories developed what is now known as LEAN. LEAN was based on five principles: 1. Identify the Value, 2. Map the Value Stream, 3. Create Flow, 4. Establish Pull, and 5. Seek perfection. Once again, the principles were very simple, but throughout the eighties, they formed the basis for the superiority of the Japanese automakers, which outmatched their American colleagues. It took the US factories 240 days to produce one car, whereas it only took the Japanese 24 hours! 1

The Japanese production costs were half those of the US, and the quality was better. Today, these principles of focusing on value adding time, cycle time, lead time, and waste reduction through continuous improvements are well-known best practices with all production management. The Japanese mantras of small batch sizes and flow struck a responsive chord all over the world.

How to live and prosper in an uncertain & rapidly changing future?

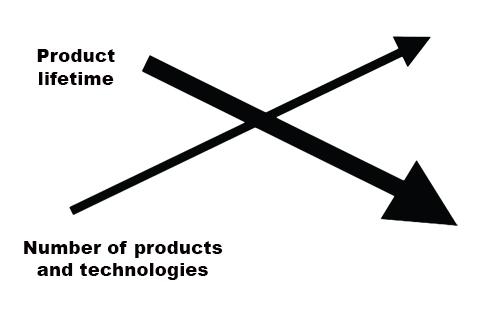

Strategies that were once needed and that worked in the past won’t accommodate the needs of tomorrow’s fast-paced environment. We’re headed for a world with no speed limits. A life where new products, tech- nologies, and needs wash over us like a tsunami. In an effort to optimize our products and processes, all these changes can feel like a never-end- ing sea of interruptions.

We’re in a position where optimization is growing increasingly desperate as service lives are continually declining. Creation is outpacing optimiza- tion. We need to understand that the efficiency paradigm is water under the bridge and that we actually live in an innovation-driven reality. It’s essential that we learn to exploit the accelerating flow of opportunities rather than viewing them as interruptions.

Out of the blue

3D Robotics is a good example of a company emerging based on a product costing only a fraction of an existing product. Every day, Chris Anderson, editor of Wired Magazine, received tech gadgets and toys for review. One day he brought home an RC model airplane and a LEGO Mindstorm set for review. His plan was to build a LEGO robot and test the airplane. He had trouble controlling the airplane, so he combined the LEGO control system and the GPS sensor from a cell phone with the airplane – and 3D Robotics was born. Suddenly, it was possible to build a drone for less than $500, even though they feature 90% of the same functions as the Raven, which comes in at $50,0008 2.

The future is made up of innovation and quick reactions

The fashion company ZARA’s business model is based on quick reactions, because fashion is notoriously unpredictable. Their business principle is to distribute limited collections to stores and observe what the customers actually buy. That way ZARA isn’t left with large collections on their hands. And they can sell everything at regular prices. For customers, this means there is always something new in the stores, which increases their visit frequency. If a customer sees an interesting product, she better buy it immediately because within two weeks the collection will have changed.

ZARA manufactures their clothing in Europe. It’s more expensive, but the supply chain is shorter. Other brands manufacture their products in China, but before the shipping container has completed its trip around the world, the fashions have changed.

It’s essential that we learn to exploit the accelerating flow of opportunities rather than viewing them as interruptions.

The response to increasing project volumes has been an explosion in concepts, certifications, and methodologies

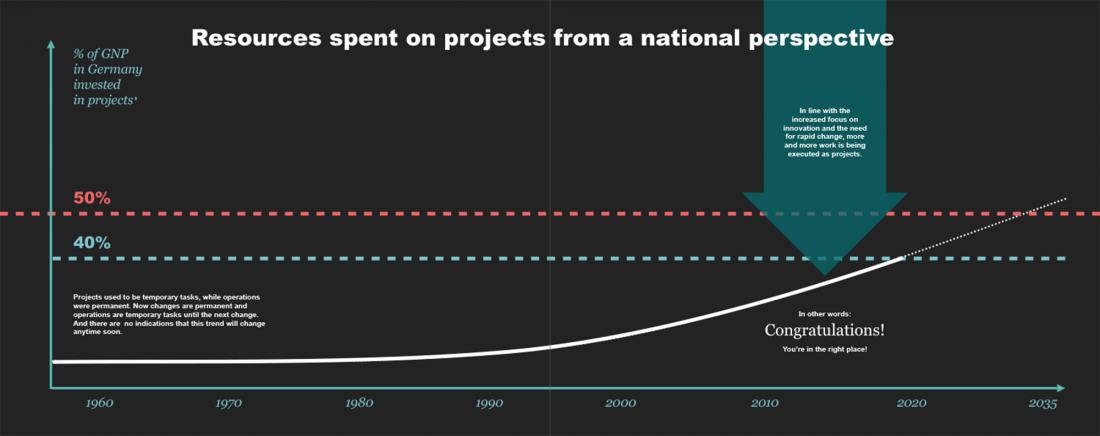

The drastic need for constant innovation and change has had a strong influence on the world of project management.

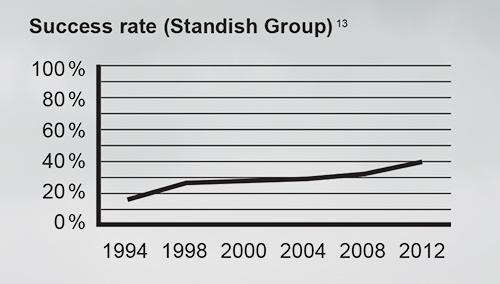

More and more work is being conducted as projects, and there has been an explosion in concepts, training, and certifications since 2000.

Several universities offer master’s degrees in project management and the number of project management programs and courses is rising rapidly. In fact, project management has become so widespread that it has evolved into a basic product with most suppliers.

The three major certification organizations

– Project Management Institute (PMI), TSO, and International Project Management Association (IPMA) – are growing constantly and have expanded with several specialist certifications, some of which are listed to the right.

Besides certifications, project managers are moving into all organizational levels. A multitude of concepts for program management, portfolio management, and organizational maturity assessment have been launched.

The PMBOK Guide does not represent the knowledge that is necessary for managing projects successfully.

Peter Morris

Before we proceed, due diligence is to ask ourselves:

Is the foundation of our project management built on the right assumptions?

What would the consequences of continuing with the current mindset be?

… luckily, there is still a huge potential to be realized

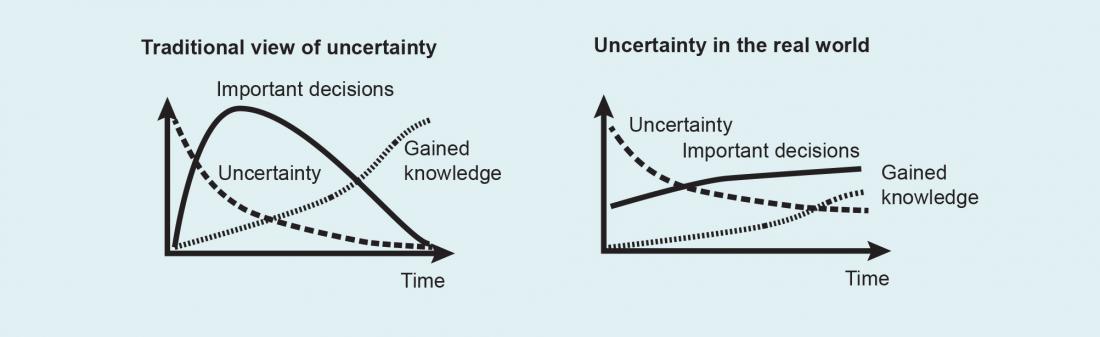

The conventional perception of project uncertainty and the importance of decisions has its foundation in the domains of engineering and construction. Contracts and predictability are based on the triple constraint and considered to be stable elements. The core idea is that it is possible to reduce internal project risks all the way to the final deliverables. All conventional project management literature aims at reducing this risk through defined methods and a consistent focus on risk management, defined processes, and frontloading of information, as illustrated in the top graph.

However, with the acknowledgement that the project’s overall purpose is to achieve an impact, comes the understanding that the risks are only reduced once that impact has been achieved. At the same time, new possibilities keep hitting the project, making knowledge obsolete and demanding the continuous reconsideration of decisions and the overall purpose. This scenario is illustrated in the bottom graph. It is essential that we create direction in this chaos. We need to focus on a flow of impacts and on the involvement of the people and stakeholders who can create the future.

The management of structures, systems, and processes is not enough. This calls for leadership – project leadership! An approach that maintains a continuous focus on making sense of the project in its current state and on its stakeholders, as well as on creating a shared vision that everyone should aim towards.

Luckily, we have a strong foundation to build on. All we need to capture the full potential is to:

Ensure that projects are carried out in order to achieve an impact and that deliverables are simply a means for reaching this goal.

Accept that, in a turbulent world, we need to create a flow of impacts, so launching new products, services, and processes becomes just as painless as the most streamlined production process.

Understand that, in a world with easy access to infinite knowledge and highly trained employees, it takes a new kind of leadership to create a common vision, backing, and stakeholder satisfaction

What are the impact objectives for your project?

Do you even measure impact?

Set the stage, involve skilled people, and create a flow of results

In 2000, Jimmy Wales had an idea for an internet-based encyclopedia called Nupedia. He wanted various experts with a profound professional knowledge to contribute and all entries should be reviewed by other experts. A thorough and serious approach – but also very slow. So in 2001, Jimmy Wales launched a small spin-off project where anybody could contribute. And Wikipedia was born! A month later, Wikipedia featured 1,000 entries. After six months, the number reached 40,000. And by 2012, it had a staggering 22 million entries. But what is truly interesting is what happens when an insufficient or poor-quality entry appears – someone is guaranteed to correct any flaws within a matter of hours. A journalist, A.J. Jacobs, actually tested this by deliberately submitting poorly written entries. In just 24 hours, his entries were corrected 225 times, and within the next 24 hours about 150 times more2 .

Jimmy Wales must have been quite taken aback by this. What happened? He planned a meticulous encyclopedia based on the very best principles and assisted by the most acute minds – so how could this project be overtaken without warning? And even more interesting: without a central plan for how the innovation work should progress!

Which principles enable this?

References

1) The Machine That Changed the World, by James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos (1990)

2) The Creative Society by Lars Tvede (2016)

3) Booz, Allen and Hamilton (1992)

4) Funky Business by Nordström & Ridderstråle (2008)

5) Education at a Glance (2012)

6) U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED).

7) McKinsey. Sweet Spot by Arun Sinha (2006)

8) Dr. Yvonne Schoper, MTV, Berlin (2015)

9) TSO, Prince2, The official website (The Stationery Office) (2015)

10) PMI, The official website(Project Management Institute) (2015)

11) IPMA, The official website (International Project Management Association) (2015)

12) The organizations’ official websites (2015)

13) The Chaos Report by Standish Group (2013)

14) Spotify YouTube (2015)

15) Half Double pilot project (2016 – 2017)

16) Reinventing Project Management by Aaron J. Shenhar & Don Dvir (2007)

17) Good Business: Leadership, Flow, and the Making of Meaning by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (2004)

18) The Leadership code by Dave Ulrich (2015)

19) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oN2gBjtwdhk